Photo: Josephine Andrew sits in the kitchen of her home of 30 years. The family is preparing to move after more than a year of severe bullying against their son — and repeated vandalism to their property. / Photo by Amy Romer

By Amy Romer

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

IndigiNews

Content warning: This story details violence against an Indigenous Youth whom IndigiNews is identifying as ‘Kai,’ a pseudonym, for his safety. Please look after your spirit and read with care.

Kai had walked Fifth Street, “Courtenay, B.C.’s” main downtown stretch, many times before.

It’s a simple route from the LINC Youth Centre to the 16-year-old’s home.

But on a warm September evening this year, as he approached the local donut shop, a fellow teen from school he’d known for years stepped toward him — carrying a knife.

Through his many experiences of bullying, Kai had needed medical attention before, including a suspected concussion and black eyes.

But never because of the use of a weapon.

Kai was stabbed just below his left armpit, close to his heart. In the days that followed, his alleged attacker — who cannot be identified under young offender laws — was charged with aggravated assault and assault with a weapon.

The accused, who is a minor, faces a nighttime curfew and must stay 50 feet from Kai. His next court date is Jan. 8, but Kai’s family has been told the case is unlikely to go to trial before next summer.

“Meanwhile, he’s walking around free,” said Josephine Andrew, Kai’s maternal great-aunt and foster mom.

It wasn’t the first time the Nuu-chah-nulth Nation member had been hurt by his non-Indigenous peers. His foster parents believe he’s targeted partly because he has a developmental disability.

He says the same boys have followed him for years, their bullying transitioning from school hallways into the community and online.

Even since the alleged attack, rocks have been thrown through the back window of his family’s vehicle.

Kai’s family has since lived in constant vigilance. Their adult son has moved home to help protect them, and the household now sleeps in shifts. Friends from their drum group have even offered to stand watch in their driveway overnight.

“It feels like in every corner there’s a battle,” said Andrew.

But what he says happened to him on Fifth Street wasn’t merely the result of bullying, Andrew believes.

To her, his experiences reflect a history of colonial systems failing to uphold the safety, rights, and well-being of an Indigenous Youth.

Those include both the school district and the child “welfare” system, which the Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded in 2015 “has simply continued the assimilation that the residential school system started.”

Josephine (left) and Robert Andrew (right), Kai’s foster parents, hold a portrait of the now-16-year-old teen outside their home in ‘Courtenay, B.C.’

‘A cesspool of emotions we’ve had to go through’

Kai and his alleged attacker go back a long way, Andrew said.

They attended middle school together. For a time, the boy would even come over to Kai’s family home to hang out and eat snacks, recalls Andrew.

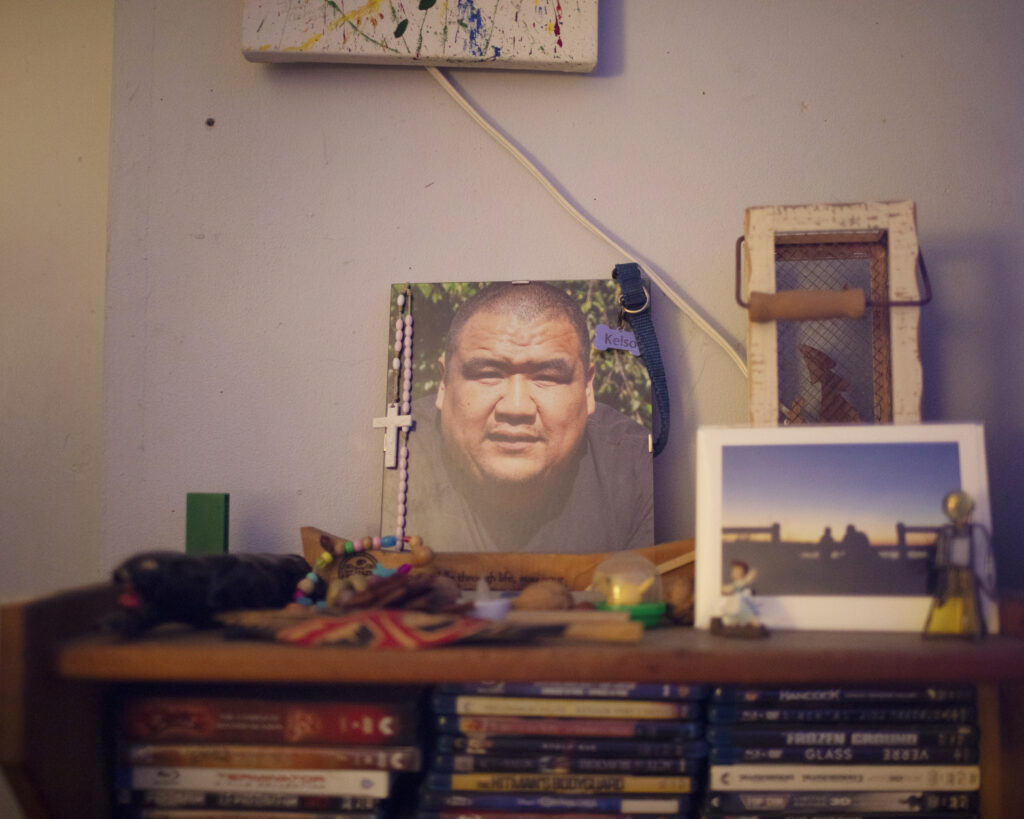

Their home is comfortable, featuring cozy rooms crowded with keepsakes, knick-knacks and framed family photos, many tracing their decades of caregiving.

Together, Andrew and her husband Robert have raised more than 52 mostly Indigenous children as foster parents.

“We stopped counting at 52,” said Andrew.

When Kai moved on to senior high school, his alleged harassment by the accused and other Youth grew more aggressive, she said — spilling from school into the community.

So she enrolled Kai in self-defence classes.

The family also faced their first round of property damage, saying rocks were thrown at their vehicle in 2024.

Kai has come home with black eyes on two occasions, Andrew said. He was hospitalized after the first incident but refused medical care the second time.

Now in Grade 11, Kai’s family accompanies him everywhere. They drive him to activities, sit with him at events, and try to stay close at all times.

But the one night his family agreed to let him walk home alone from the Youth centre downtown was the night he was attacked.

They say they haven’t let him out of their sight since.

“We shouldn’t have to do this,” Andrew said.

Andrew believes the charges laid against the accused — aggravated assault and assault with a weapon — don’t go far enough.

“It’s been a cesspool of emotions we’ve had to go through,” said Andrew.

In an email to IndigiNews, a spokesperson for the B.C. Prosecution Service said that “charges will only be approved if Crown Counsel is satisfied that the evidence gathered by the investigative agency provides a substantial likelihood of conviction and, if so, that a prosecution is required in the public interest.”

Despite this, Andrew feels the RCMP’s response has been inadequate — particularly given the vandalism that’s occurred on their property.

“I try not to go to racism, but there’s a difference in the way things are handled,” said Andrew. “We feel discarded.”

IndigiNews reached out to Comox Valley RCMP repeatedly throughout the reporting of this story, by phone and email since October, but did not receive a response in time for publication.

Andrew partly blames Kai’s school for the bullying going as far as it did, as she said the school has been aware of Kai’s alleged bullying for years, with little consequence.

IndigiNews requested interviews with both the school and School District 71 (SD71), but received only an emailed statement in response.

“Comox Valley Schools is aware of the recent community incident currently under investigation by the RCMP,” the statement read. “Due to privacy considerations and the sensitivities involved, the district is unable to comment on specific students or circumstances.”

The district said its schools are “committed to ensuring safe, inclusive, and caring learning environments for all students.”

“The district’s policies and procedures emphasize respect, equity, and the well-being of every learner, with specialized supports and collaborative partnerships across schools and the community.”

‘Nobody’s going to listen to me anyway’

As Kai’s alleged bullying continued through secondary school, the accused and his friends learned how to provoke him, Andrew said.

Kai, who loves both playing and following sports, has complex support needs, she explained; although he is 16, he functions at the level of an eight-year-old.

“He doesn’t have the skills to respond,” she said, “so he would react.”

When this happened, Andrew said, it’s often Kai who ended up being disciplined by teachers — frequently by being sent home.

He’s also been told by teachers to act his age, Andrew said.

“He learned that he was the bad kid,” she said. “He’d say, ‘Nobody’s going to listen to me anyway.’ And I think that must happen to a lot of kids.”

A 2009 study of adolescents in urban high schools on the “U.S.” West Coast found that students from ethnic minority backgrounds were more likely to ask teachers or school staff for help when they felt the adults were fair and took bullying seriously.

Those who trusted school authorities to intervene, were also less likely to fight back against their peers.

Neither the school nor SD71 would comment specifically on Kai’s alleged bullying.

“Comox Valley Schools takes all concerns related to bullying and student safety seriously,” it wrote in an email statement.

When concerns are raised, SD71 said its staff respond promptly, and engage with parents and guardians as appropriate; students involved are connected to counselling from trusted adults or external support as needed.

Andrew says in her experience, it depends on the staff member. Last year, she added, as the bullying escalated, she didn’t always see eye-to-eye with Kai’s caseworker when they communicated.

Purple ribbons encircle a tree for a school-wide reconciliation event, held in October. The event ‘honoured residential school survivors, remembered the children who never returned home and reaffirmed the school’s commitment to ongoing Truth and Reconciliation,’ said a School District 71 spokesperson.

‘If that’s not segregation, I don’t know what is’

Kai’s developmental differences means he is enrolled at school under the Practical, Real-life, Educational, and Personal development program (PREP).

It’s meant to support students with diverse learning needs who benefit from “functional academics, life skills, and pre-employment experiences,” wrote SD71 in an email, preparing them for life beyond school.

Andrew believes the program, which she said has about 10 students enrolled in the school, “feels like a dumping ground for kids they don’t know what to do with.”

“Placement in PREP is determined through a supported transition process and in consultation with the school-based team,” wrote SD71.

After a wave of bullying in 2024, Andrew alleged that Kai’s PREP program case worker began locking Kai in the PREP room away from his peers at lunchtime — “under the guise of protection,” she said.

Around the same time, Andrew received an email from a teacher — which IndigiNews has reviewed — asking Kai to come through the back door of the school when he arrives in the morning, and leave through the same door at the end of the day, for his safety.

“If that’s not segregation,” said Andrew, “I don’t know what is.”

Neither Kai’s school nor SD71 would comment specifically on these allegations.

Advocacy groups say Kai’s experience reflects a broader pattern in “B.C.” schools. According to the BCEdAccess Society, children and Youth with disabilities continue to be routinely excluded from education, including practices such as isolation, partial school days, restraint, and seclusion. The measures are often framed as “support” or “safety,” the advocacy group said.

In the 2021-2022 school year, for instance, the group documented 4,760 incidents of exclusion involving disabled students across the province.

The society’s data also shows that Indigenous children and Youth are overrepresented among those who experience restraint or seclusion — a disparity the advocates link to systemic inequalities and a lack of consistent, enforceable provincial policies governing such practices.

Under SD71’s administrative procedures, the district states “it has a responsibility to maintain safe, orderly and caring school environments for all of its students and employees.”

“The District recognizes that the use of emergency physical restraint or seclusion procedures may be necessary when a student presents imminent danger to themselves or others,” it stated.

“Every effort is made to employ preventative actions that preclude the need for the use of physical restraint or seclusion.”

Last year, at the end of May, Andrew decided to pull Kai out of school entirely.

“Of course he doesn’t want to go to school,” she said.

But with every suitable alternative program at capacity — and none which could meet Kai’s developmental needs — she felt little choice but to send him back into the same school.

“I hear that story from so many people,” said Andrew. “That they had to pull their kid from school because of bullying.”

Bullying data regarding SD71 students isn’t made public, SD71 told IndigiNews.

But in its 2024 Enhancing Student Learning Report, the district states there’s been a “downward trend of Indigenous students not living on reserve reporting that they feel safe” across middle and high school grades since 2021.

“We recognize that there are inequitable learning outcomes in our system that require our attention, support, and commitment to change,” the report concludes.

“We are excited about the direction we are taking as we collaborate with community to enhance support and improve outcomes for the learners entrusted in our care.”

And while SD71 does not publish specific bullying data, other districts across the province do.

For example, in the Sea to Sky School District (SD48), the most frequently reported types of bullying are verbal bullying, including threats and teasing, and social bullying, including exclusion and gossip.

Nearly 20 per cent of students reported experiencing these forms of bullying — the same types Andrew said Kai faces at school.

The incidents often trigger Kai to react, which in turn get him into trouble with authorities.

“The district provides a range of supports for students with diverse abilities and backgrounds, including Indigenous learners and those with special needs,” wrote SD71.

“We are steadfast in our commitment to equity, inclusion, and the continual improvement of our practices to ensure that every student feels safe, valued, and supported at school.”

‘A sense of belonging for Indigenous kids’

Although Kai is Nuu-chah-nulth and in his final year of senior high, he was only able to enrol in the Indigenous Education Program (IEP) this year — and only after Andrew complained, and new administrative staff were hired.

Andrew knew the program well — in fact, she said, she’s one of its original founders.

“The Indigenous Education Program didn’t even know Kai existed,” said Andrew.

Founded in the 1980s in “Port Alberni,” the Indigenous Education Program was instrumental in bringing culturally safe, culturally relevant education to Indigenous students across “Vancouver Island,” and remains in place within its school districts today.

“The idea was that we created a sense of belonging for Indigenous kids.”

Andrew and about a dozen women including Julia Atleo and Eileen Haggard — both Nuu-chah-nulth — helped create and build the program; many went on to be leaders in Indigenous education.

According to the school district’s Indigenous Education website, more than 40 staff support over 1,800 self-identifying Indigenous students. SD71 will not release how many Indigenous students are enrolled in the IEP at any particular school in the district, including Kai’s.

SD71 said the IEP supports Indigenous students through personalized learning, cultural advocacy, and land-based opportunities, while working with staff and local Nations to integrate Indigenous perspectives across their schools. Field trips and lunch time groups are also available at Kai’s school.

But Andrew said that until this year, Kai, as a student of the PREP program, couldn’t access the IEP.

“It shouldn’t have taken what it did to get him onto the program,” said Andrew, adding that Kai’s enrollment came only after a change in administration who had previous ties to Andrew, helped secure his placement.

“They’re now trying everything they can in their power,” said Andrew.

“But it should never have gotten to this point. And I shouldn’t have to have connections to make sure our kids are okay.”

Since his enrollment this year, the IEP has given Kai a sense of belonging in the school building, Andrew said. He’s connected with a program support worker and can have lunch with his friends.

Andrew, who has helped establish the program at several schools, said the program’s results have been notable.

At one school, she said, students enrolled in the IEP under her guidance graduated with a 100 per cent pass rate.

“We built a program for Indigenous kids to thrive and survive,” said Andrew, reflecting on Kai’s experience in SD71. “And instead, you’re just kicking out the kids.”

It’s not only at school that Andrew has dedicated her time to improving the lives of Indigenous children.

As well as the dozens of children they’ve raised in their home, they’ve always had an “open door policy,” according to Andrew’s husband, who said children in the wider community have always visited their home to feel part of their family.

“We don’t lock our front door,” he said. “Kids in the community come here to eat, be safe, and feel loved.”

But that openness has shifted dramatically, the family enduring what Andrew’s husband called “a complete 180” — installing cameras to monitor their driveway and front doorstep for threats to their safety.

It was on that same doorstep, in 2009, where Kai was brought here as a baby by Andrew’s niece.

At 13-years-old, she’d been placed under the “care” of the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD), who placed her with a non-Indigenous family.

In that placement home also lived a 21-year-old man. Within a year, she was pregnant.

Andrew said she warned the ministry that “an adult man had access to her” and that the young teen lacked “guidance” from other adults there.

Nine months later, she showed up on Andrew’s doorstep with Kai in her arms. Within a few days, she left and never returned.

IndigiNews tried to verify whether the 21-year-old was charged with sexual assault of a minor, but could not confirm.

“I knew in my heart that it was something she had planned,” said Andrew. “She knew we’d take care of him.”

‘He’s got all these cards stacked against him’

The Andrews are still trying to adopt Kai as their son, a process they’ve been attempting for 14 years.

“It’s been such a fight to keep our boy in our care,” said Andrew. “He’s got all these cards stacked against him.”

At eight years old, Kai was diagnosed with FASD.

The lifelong neurodevelopmental condition is caused by prenatal alcohol exposure, and affects memory, learning, emotional regulation, and social interactions.

According to a 2024 study by the Canada FASD Research Network, the prevalence of FASD among Indigenous children is significantly higher than among non-Indigenous children.

Various studies have estimated FASD anywhere between one per cent to 27 percent depending on the study location — compared to just 0.1 per cent for non-Indigenous children.

Advocates say such stark inequalities are the result of colonialism and intergenerational trauma.

“FASD among Indigenous Peoples is the result of a unique set of historical and ongoing colonial systems, policies and practices,” states the Canada FASD Research Network.

“Many Indigenous peoples have led efforts to resist these colonial circumstances, and to push back against deficit-focused narratives.”

In Kai’s case, his FASD is a result of alcohol abuse by his mother — a child when she was pregnant — who was in government custody at the time.

Andrew said she’s always known that alcohol was the cause of Kai’s developmental differences.

A 2022 report by the Representative of Children and Youth (RCY), Hands not Hurdles: Helping Children with FASD and their Families, noted that “children and Youth with FASD in schools are often ridiculed, left out and shamed by their peers, leading to social isolation and poor mental health.”

They can also be excluded by their teachers, the report says, “who may not have the knowledge or capacity to support their unique learning needs.”

Many doctors won’t diagnose children with FASD until they’re at least eight years old, according to the B.C. Children’s Hospital’s research institute.

Without a formal diagnosis, the RCY report says that “children and Youth with FASD can be perceived as behaviourally challenging rather than being understood as needing supports for their brain injury.”

In addition, children and Youth with the condition often experience educational setbacks earlier, as well as social marginalization, and heightened vulnerability to bullying.

Indigenous people with FASD are also vastly overrepresented in the justice system — particularly the Youth system — a pattern that underscores persistent inequities in how society protects Indigenous Youth.

‘If you have the patience to get them to adulthood, they can shine’

Until a few years ago, the Andrews’ relationship with Kai’s social workers had been fraught.

“It was like that for the first ten years,” said Andrew. But over time, things began to change.

In 2019, amendments to the Child, Family and Community Service Act, along with new Indigenous-led practices and expanded family-support funding, came into force.

The changes required MCFD to work more collaboratively with First Nations, intervene earlier with supportive services rather than removals, and ensure children remained connected to their community and culture.

It’s possible Andrew was feeling these changes on the ground, but for Andrew, it felt like “too little, too late.”

She also wonders whether this is a similar experience to other local families, or if the improved relationship was because she simply pushed back so hard.

“They don’t ruffle our feathers anymore,” Andrew said, “because we will fight.”

She said Kai will be the last child the couple raise.

“They all have gifts,” said Andrew’s husband, reflecting on the many children they raised together. “And if you have the patience to get them to adulthood, they can shine.”

But because of the recent threats, the couple recently decided to move away from their home of 30 years, “essentially for our own protection,” he said.

“We’re old farts. We thought we’d be here forever.”

Andrew says she feels anxious knowing the boy accused of Kai’s stabbing will be “roaming the streets” until next summer.

“I’m tired,” she said. “Really, really tired.”

But her family has not been without community support.

Andrew’s relatives and the local Indigenous community have been “up in arms,” rallying in front of the courthouse during the Nov. 27 court hearing.

And the business community of downtown Courtenay — where Kai’s alleged attack took place — recently surprised him with a gift basket, put together to show support.

“The gifts are beautiful but are outshone by the pure love it contained,” Andrew wrote on Facebook.

“I still haven’t gone through the entire basket because I break down and cry,” she later told IndigiNews, adding that both a local boxing club and tae kwon do school have both offered Kai free lifetime memberships.

“Of all the bad things that happen, there is always more beauty,” said Andrew.

“We just have to trust.”

Editor’s note: This story was produced as part of Spotlight: Child Welfare, a collaborative journalism project that aims to improve reporting on the child ‘welfare’ system. Tell us what you think.