Photo:

By Trent Wilkie

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

St. Albert Gazette

Alberta is set to allow hunting of farmed elk and deer within fenced enclosures.

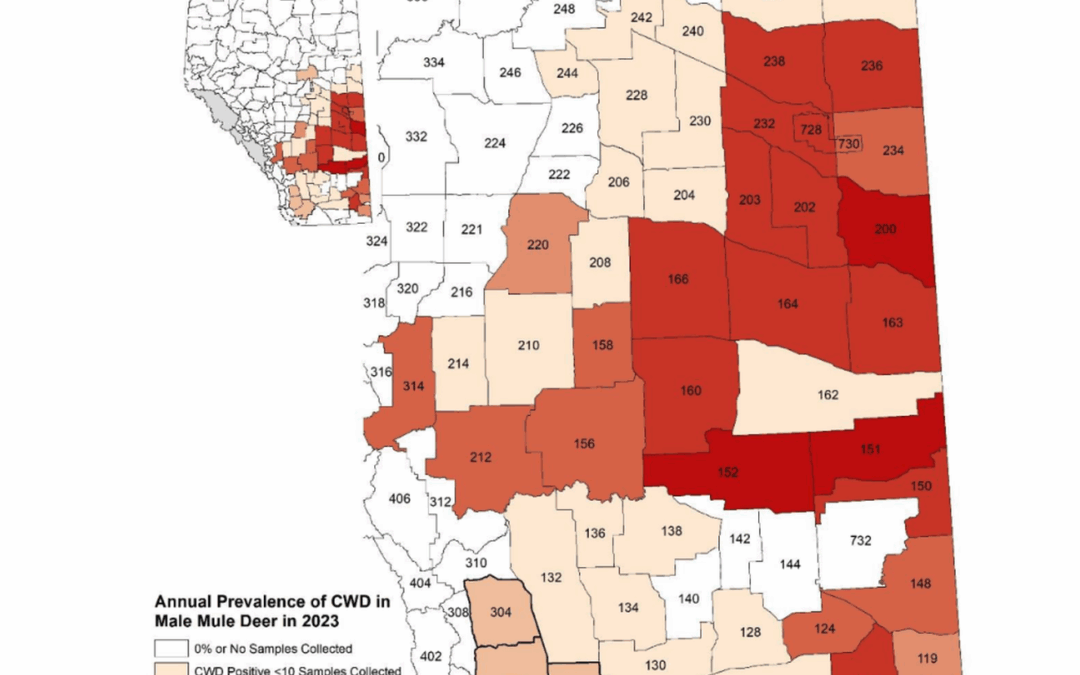

The proposal is part of Bill 10, a red tape reduction bill introduced Monday, and would allow “harvest preserves” — fenced areas where hunters can pay to shoot farmed elk and deer. The province says the move will create new revenue for cervid (members of the deer family) producers and boost rural economies, but critics warn it could spread chronic wasting disease (CWD) to areas where the fatal illness isn’t yet present.

“It’s a very prevalent disease in the central southeast and basically all the South,” said Pamela Narváez-Torres, a conservation specialist with the Alberta Wilderness Association. “We’re concerned about moving CWD-positive animals to parts of the province where the disease isn’t present yet. We still have healthy herds, and we want to keep it that way—especially for caribou.”

Narváez-Torres, who has a master’s in anthropology and a bachelor’s in biology, said CWD is a fatal neurological illness that affects deer, elk, moose and caribou. It causes severe weight loss, disorientation and death, and there is no cure or vaccine.

“CWD is caused by abnormal proteins called prions, which can be found in soil, plants, hair, saliva and urine,” she said. “Once it reaches the soil, you can’t remove it. Once it goes into a plant, you can’t remove it. It stays in the soil for a long time.”

The disease was first detected in Alberta in 2002 in farmed elk and deer and later in wild deer in 2005. It has since spread across southern and central parts of the province, with some areas reporting infection rates as high as 85 per cent in mule deer. Surveillance data from 2024–25 recorded 472 positive cases, including 353 mule deer and 94 white-tailed deer. Experts say the trend has been rising since 2016.

“You can’t tell if an animal is infected with CWD unless the animal is dead and has been tested,” Narváez-Torres said. “If it comes from a CWD-negative farm, you might have a good chance of the animals not having the disease, but it could be present in feed, as in plants. They could be feeding it to the animal not knowing.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says there are no confirmed human cases, even in areas where hunters regularly consume venison from CWD-positive regions. But experts consider it a theoretical risk because CWD is similar to mad cow disease, which crossed the species barrier in the past. The CDC advises hunters not to eat meat from animals that test positive or appear sick, wear gloves when field dressing, avoid handling brain, spinal cord or lymph tissue, and follow testing requirements.

“I don’t think the province has the capacity to process absolutely every single animal that gets hunted in the province,” Narváez-Torres said. “I’m not sure who’s going to pay for this extra testing that they’re going to be doing.”

More information on CWD is available at MyHealth.Alberta.ca.