Photo: The shoreline at Tl’uqtinus village — once the annual home to more than a thousand people during salmon season — is today a tangle of blackberry bushes and shipping terminals in what is today ‘Richmond, B.C.’ The riverside village of Tl’uqtinus — once the annual home to more than a thousand people during salmon season — is today a sprawl of retail warehouses, mostly unused municipal lots, a Coca-Cola plant, and a fuel facility for the nearby Vancouver International Airport. The village site of Tl’uqtinus, a now-industrialized area on the ‘Fraser River’ in ‘Richmond, B.C.’ Photo courtesy of Brian Thom

By David P. Ball

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

IndigiNews

Less than 15 kilometres up the “Fraser River” from the Salish Sea, the former fishing village’s once-busy shores are today host to shipping terminals and a tangle of thorny and invasive blackberry bushes.

Last week, Tl’uqtinus village sparked an even thornier public debate over Indigenous people’s right to land — and settlers’ private property — across the province.

The B.C. Supreme Court, after a record-length trial, declared the Quw’utsun (Cowichan) Nation holds title to the 7.5-square-kilometre village site and the right to fish near it — a century-and-a-half after the province sold it to settlers.

Four First Nations within the nearly-9,000-member Quw’utsun Nation celebrated their victory after six years in court.

What was unique about the case was that the plaintiff’s “Vancouver Island” reserves — which include the province’s most-populated First Nation — sit more than 60 kilometres southwest of Tl’uqtinus, across the Salish Sea.

The court reviewed historical documents, oral histories, and expert witnesses testifying that “many, many canoes” used to cross the strait to the mainland during salmon-fishing seasons.

“For over 150 years, we’ve been pushed away from Tl’uqtinus,” Chief Laxele’wuts’aat (Shana Thomas), of Lyackson First Nation, told reporters on Aug. 11. “Our lands were taken, our fishing rights were denied, our voices were silenced — but we remembered … Tl’uqtinus is ours.

“This is not just a legal victory; this is a spiritual homecoming.”

Leaders from Quw’utsun (Cowichan) Nation and their lawyer stand after an Aug. 11 press conference about their Supreme Court of B.C. victory. From right to left: Chief Shana Thomas (Lyackson First Nation), Chief Cindy Daniels (Cowichan Tribes), Chief Pam Jack (Penelakut Tribe), and Chief John Elliott (Stz’uminus First Nation), and lawyer David Robbins (Woodward & Company). Photo by Eric Richards/The Discourse

A landmark precedent for other First Nations

According to Justice Barbara Young’s decision, the government’s “fee-simple” private land grants of the village site to settlers, starting in 1871, were “defective and invalid.”

They “deprived the Cowichan of their village lands, severely impeded their ability to fish the south arm of the Fraser River, and are an unjustified infringement of their Aboriginal title,” she wrote in her Aug. 7 ruling.

Her 863-page decision came after 513 days of trial hearings — a record duration in the country.

“The province has no jurisdiction to extinguish Aboriginal title,” she concluded. “The Crown grants of fee simple interest did not displace or extinguish the Cowichan’s Aboriginal title.

“Aboriginal title lies beyond the land title system.”

The ruling was seen as a major precedent for other First Nations claiming title to specific historic sites — even if they’re not geographically connected, or contiguous, with most of their territories.

“It’s potentially a Pandora’s box decision,” said hagwil hayetsk (Charlies Menzies), a University of B.C. anthropology professor and member of Gitxaała Nation.

“In the past, the colonial courts have argued you have to define it as though you are a nation-state, and you have to have exclusive, territorial, contiguous territorial spaces,” Menzies told IndigiNews.

“What this case shows is you don’t need contiguous space … There’s no part of this province that doesn’t have a similar situation at play.”

He compared its importance to Tŝilhqot’in Nation’s ground-breaking land title victory in the Supreme Court of Canada in 2014 — and to that court’s 1990 fishing rights decision in favour of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) gillnetter Ronald Sparrow.

Legal expert John Borrows — author of Canada’s Indigenous Constitution and Loveland Chair in Indigenous Law — told IndigiNews the decision builds on the precedent set by the Tŝilhqot’in decision 11 years ago.

“Courts have been slow to recognize that property law’s protective frameworks also apply to Indigenous peoples in Canada,” said the University of Toronto law professor, and member of Chippewa of the Nawash First Nation, in an email.

“This decision strengthens property rights by recognizing it has a deeper time frame in Canada, that pre-exists the country’s creation.”

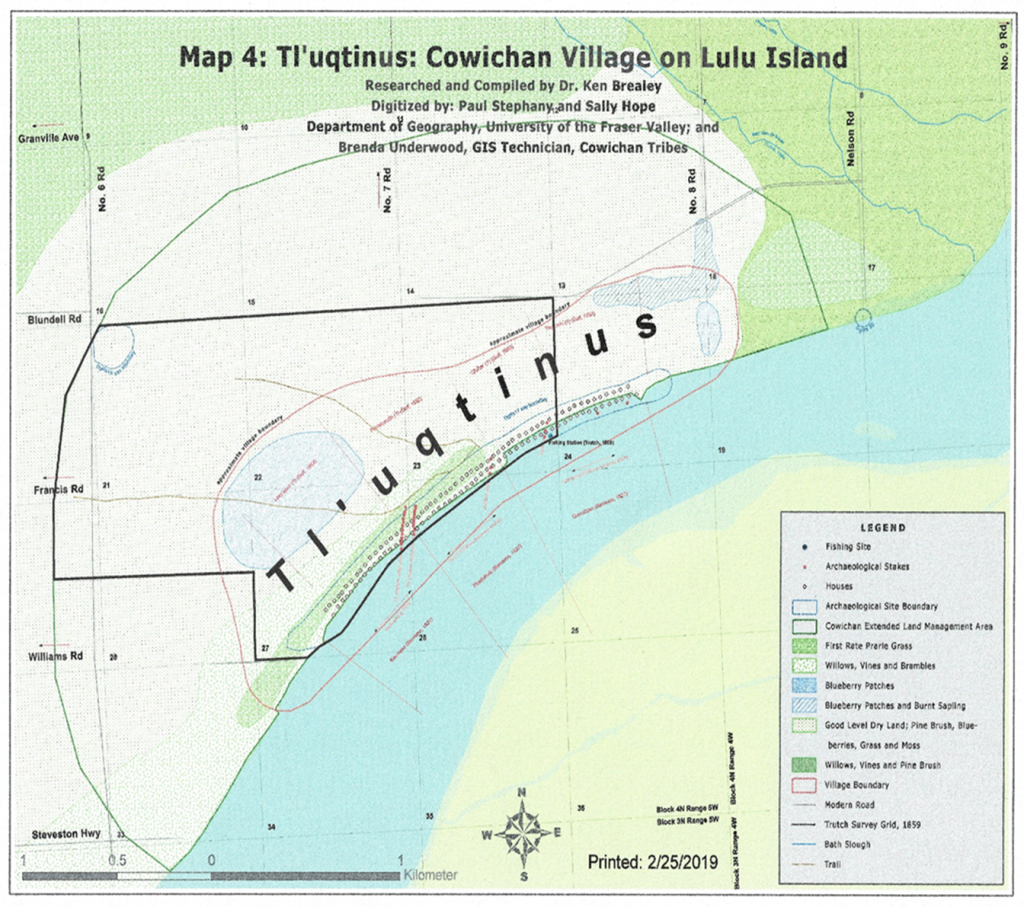

A map in the B.C. Supreme Court decision shows the boundary of the former village of Tl’uqtinus (red line) on the in ‘Richmond, B.C.’ Its surrounding extended land-management area is marked by a green line

Conflicting Indigenous claims

But the ruling drew the ire of two other Coast Salish communities — xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam Indian Band) and scəw̓aθən məsteyəxʷ (Tsawsassen First Nation) — who claim the Tl’uqtinus lands and waters as their own.

They worry about its precedent for their own title and rights on their territories.

“It’s so frustrating,” yəχʷyaχʷələq (Chief Wayne Sparrow) told IndigiNews in an interview.

“Having other communities coming to our territory and claiming it — in the heart of our territory — is disheartening.”

He did not think the judge took adequate account or consideration of his members’ oral testimonies during the case.

Sparrow said his nation never denied that Quw’utsun members stayed in Tl’uqtinus village during salmon seasons.

But he said they were actually relatives of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm families, and were permitted to stay temporarily in the village — comparing it to putting up visiting relatives in a hotel today.

“Our Elders around the table said it wasn’t the whole Cowichan Tribes — it was kinship and family ones who came over to get their fish in the summertime,” he said. “There were designated spots.

“It’s sad we’ve come today to not looking at resolving it ourselves, we’re involving the court system.”

He said to his knowledge, Musqueam always allowed other First Nations to fish the river when asked.

“We’ve never denied anybody access if they came and talked to us,” Sparrow said. “But now some of them say, ‘We don’t need to talk to you because it’s ours.’

“Now we have judges deciding what our history is.”

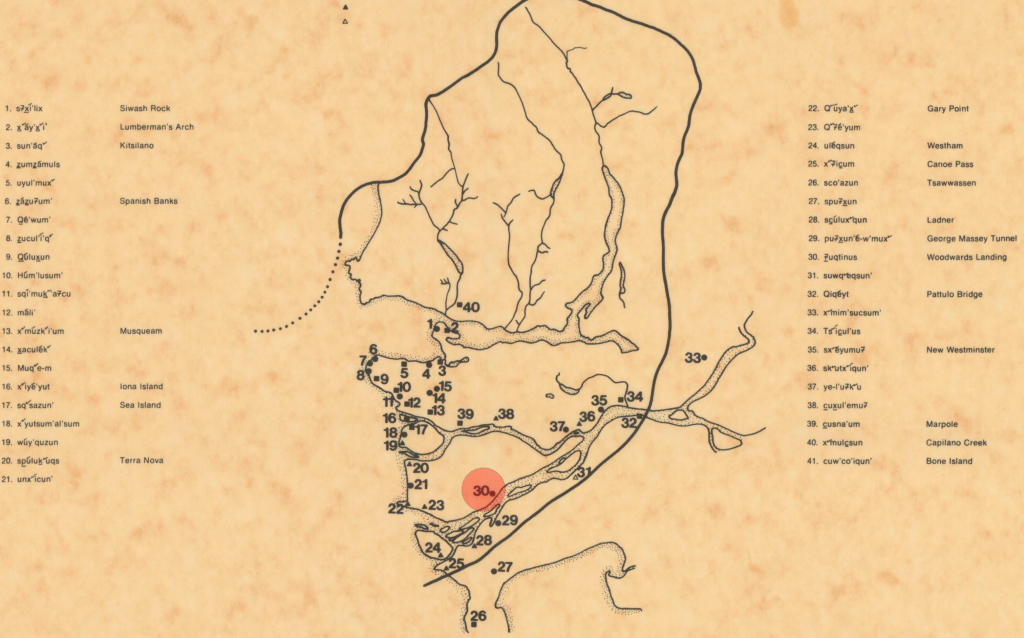

The former village of Tl’uqtinus (here spelled 7̵uqtinus, highlighted in red) is included in the 1976 Musqueam Declaration’s map of villages across xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) territories — sites to which the document’s signatories declared ‘aboriginal title to our land.’

Justice Young not only sided with Quw’utsun title to Tl’uqtinus, but also their “right to fish the south arm of the Fraser River for food … Historically, they did not nor do they now require the permission of Musqueam.”

Tsawwassen First Nation (TFN) declined an interview, but in a statement said it’s reviewing the ruling.

According to Young’s summary of its position, TFN had argued “the evidence does not establish that the plaintiff bands and Lyackson are a proper collective rights holder. TFN submits that there is no self‑governing entity known today as the Cowichan Nation.”

For Penelakut First Nation’s Chief Chakeenakwaut (Pam Jack), the case was never intended to divide Coast Salish communities — nor to take away anyone else’s rights. From the beginning, the plaintiffs opposed both Musqueam and Tsawwassen’s requests to be added as defendants.

“We’re not here in opposition of anybody,” she told reporters on Aug. 11. “We’re not here to fight amongst ourselves, we’re not here to fight against anyone.

“We’re here to ensure that history is in its right place … for our feet to be on the land where we rightfully belong.”

As Menzies sees it, the decision could potentially pave the way for a more nuanced legal understanding when multiple First Nations claim title over the same areas, “toward figuring out a way to understand overlaps in territory.”

Members of Stz’uminus First Nation, part of the Quw’utsun Nation, visit the former site of Tl’uqtinus village in ‘Richmond, B.C.’ in 2013.

Settler fears for landowners

Young’s decision immediately sparked intense controversy among the province’s settlers, too.

The opposition B.C. Conservative Party decried the ruling, with its Indigenous relations critic Scott McInnes saying on Aug. 9 it set a “dangerous precedent” for landowners’ rights and would “place vital infrastructure at risk.”

“Reconciliation cannot be achieved through division,” he continued, “or by stripping rights from one group to grant them to another.”

Newspaper columns warned the ruling was an “axe to private property,” could “scare the general public and businesses,” and declared that reconciliation itself “looks like the end of property rights.”

Some columnists, however, urged critics to “calm down” and not “overstate the significance” of the ruling.

Within days, the province announced it would appeal, citing concerns over “protecting and upholding private property rights” — launching what could be many more years of hearings in the B.C. Court of Appeal, and potentially the Supreme Court of Canada.

But Young specifically declared there was no threat to private property owners in the city of “Richmond, B.C.,” which opposed the title claim over part of the city’s riverfront.

The argument “that a declaration of Aboriginal title will destroy the land title system … wreak economic havoc and harm every resident in British Columbia is not a reasoned analysis on the evidence,” she wrote. “It inflames and incites.”

The judge emphasized that “Cowichan have not made a claim for return of land from non-parties and the property rights of the private landowners are not undermined.”

The ruling listed 86 lawyers involved in the case — nearly three-quarters of them for the lawsuit’s respondents.

Menzies questioned the province’s appeal, particularly based on concerns about fee-simple property rights.

“I can’t think of how expensive that trial has been,” he said, “and it’s going to keep costing money because of the province’s god-forsaken idea that it’s decided to try to move to appeal it.”

He added that fears for landowners’ property rights aren’t the fault of Indigenous communities whose lands were stolen and sold to settlers.

“It is the responsibility of the colonial governments to resolve the problems they created,” he said.

“If you bought something illegally, even if you were not party to it, there are still consequences for buying illegal goods.”

In an Aug. 11 press conference, the province’s attorney general said she opposed the decision — saying land claims should not be addressed through courts, but through negotiations that protect private property.

“Our government is committed to protecting and upholding private property rights, while advancing the very important and critical work of reconciliation here in this province,” Niki Sharma told reporters.

A century of protest, petitioning premiers — even a plea to the king

The court challenge started six years ago, when four Quw’utsun Nation bands took the provincial and federal governments to court.

The quartet — Cowichan Tribes, Stz’uminus First Nation, Halalt First Nation, and Penelakut Tribe — also named Lyackson First Nation as part of their title claim. The City of Richmond, Musqueam, Tsawwassen and Vancouver Fraser Port Authority were later added as defendants.

But the legal battle was far longer than six years in the making.

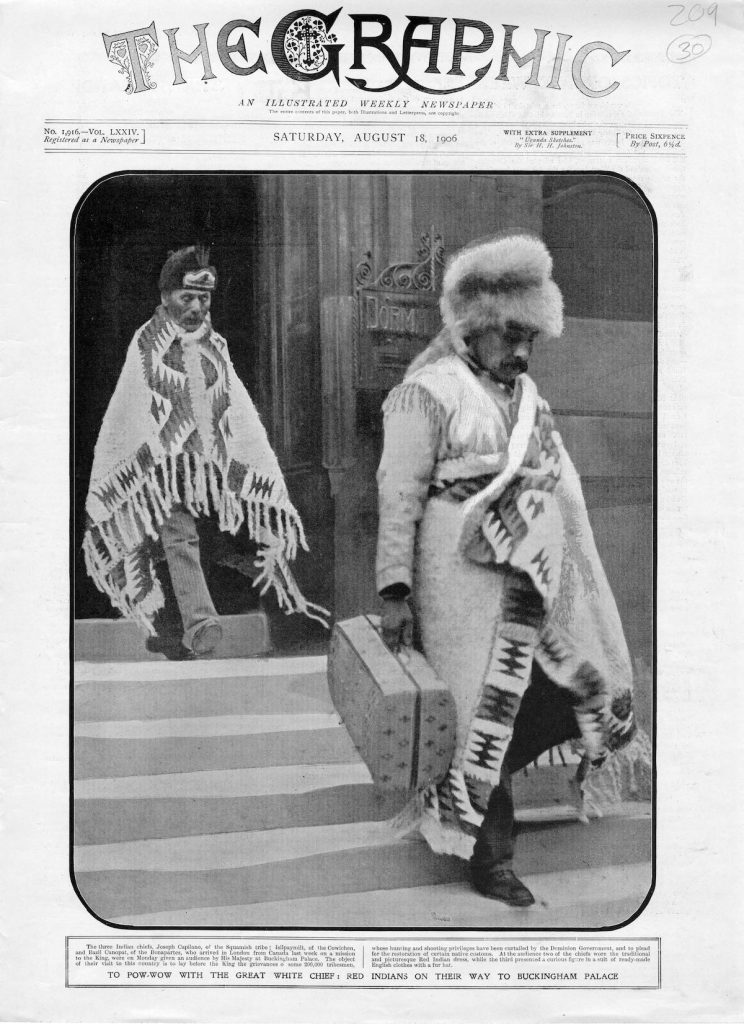

The lawsuit came after more than a century of trying to regain the village lands through other avenues: petitions to the premier, treaty negotiations, and even an audience with the late King Edward VII in Buckingham Palace in 1906.

Chief Charley Tsilpaymilt of Quw’utsun Nation (left), and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation Chief Sa7plek (Joe Capilano), leave Buckingham Palace days after meeting King Edward VII on Aug. 13, 1906. They traveled to England “to lay before the King the grievances” of Indigenous people whose harvesting rights and cultural practices were “curtailed by the Dominion Government.”

Brian Thom, chair of the University of Victoria’s anthropology department, remembers Quw’utsun Elders speaking about the importance to them of the mainland village site as he researched his doctoral dissertation with them 25 years ago.

“The recognition of that history of what happened there was very important to them,” he said. “It’s an egregious theft, a colonial taking of land.”

He said the Tl’uqtinus challenge is important for asking what is Indigenous title to specific historic places — not just broad swathes of traditional territories as was won in the Tŝilhqot’in court victory.

But it’s also trailblazing, he believes, because of Justice Young’s consideration of Indigenous legal orders.

“This judge took a dive — not only into the oral histories to look for facts and the archaeology and the ethnographic descriptions,” he said. “But she then tried to understand, ‘What is Coast Salish law on these matters? How does the property system work for Coast Salish people?’

“What’s interesting is maybe [this] shifts our attention away from these ugly terms in English like ‘seasonality,’ which I think is a highly problematic term — and has us focus on issues of Indigenous law.”

A Quw’utsun man stands on a salmon-fishing weir near a canoe, on the Nation’s territories on the Cowichan River in the late 1860s.

‘Our health is tied to the fish’

As parties to the massive legal dispute brace for years of likely appeals in the case, the river near Tl’uqtinus village is bustling with Coast Salish fishers harvesting sockeye salmon as they have for millennia.

At the heart of the legal dispute, the Tl’uqtinus site sits merely “about a mile downriver” from where Ronald “Bud” Sparrow was arrested while fishing in 1984, sparking Musqueam’s precedent-setting legal battle, explained the nation’s chief.

“It’s almost the exact same area — get in a boat and you’d be in the Sparrow area in minutes,” Wayne Sparrow said. “We lost in the Sparrow case … in lower courts, too, but won in the Supreme Court of Canada.

“Our community will fight until the fight’s over. And the fight’s not over.”

This year’s sockeye run is already providing an unexpectedly bountiful harvest, the chief told IndigiNews after a weekend fishing the “Fraser River” with his son and two nephews.

Harvesters from his nation aren’t just fishing for themselves, but also for other First Nations in the region, too.

“We’re helping them prepare for winter,” Sparrow said, as he drove to pick up salmon to be processed by community members. “My father always said our health is tied to the fish.”

Within a day of the court ruling, Quw’utsun fishers were out on the river too, celebrating their win to ply the waters off Tl’uqtinus.

“I’m happy to say that the [Quw’utsun] have been engaged in their fishery on the river this past weekend due to this judgment,” their lawyer, David Robbins, told reporters.

Through their determination and dedication, he continued, “is transformative change at their homelands and waters at Tl’uqtinus … even in the face of over 150 years of government lawlessness.

“What happens next is to be determined.”

For Tholmen (John Elliott), chief of Stz’uminus First Nation, the Quw’utsun people are taking time to savour their victory — before their legal quest continues.

“To fish on the Fraser again where we historically did … to gather and to harvest and to do the things our people did, for us it’s a day of celebration,” the leader, fisherman and hunter told reporters.

Then he spoke of his Quw’utsun ancestors, pausing for 14 seconds as he choked back tears.

“We knew it as a people, that someday — someday we’ll be back on the river, doing what our ancestors did.”