By Dan Jones.

WARNING: Disturbing content

Advocates and researchers are imploring Parliamentarians to increase public access to Indian Residential School records, as First Nations and Indigenous groups seek to identify children or remains discovered in unmarked graves and brutal sites.

Former Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Marc Miller has committed to releasing millions records that the Ministry has to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. But what researchers are discovering through Access to Information is that the federal government is very reluctant to release documents, especially if the requests impact other federal ministries.

Edward Sadowski, a researcher working with survivors of the Shingwauk residential school in Ontario said the government is not making available records for Indian hospitals and sanatoriums. “This information is there and should be made available to Indigenous People across Canada in order to honour children who died at residential schools,” Sadowski said Tuesday to a Senate Committee.

Historian Ryan Shakleton said Ottawa needs to be broader in its allowance in accessing records, as each First Nation may be looking for different documents, depending on their project scope and history of the residential school. He pointed to medical records, or documents from a neighbouring shooting range. “This has to be a much larger position around medical records, around community, municipal records. The churches need to hand over more. The churches have not handed over everything and we have evidence of that,” Shackleton said.

Sadowski explained that privacy legislation permits the Minister, in which the Ministry the information request has been made to, can release records. Yet Shackleton believes there is a hesitation or fear that a Ministry may face potential litigation for releasing documents, making it easier to deny certain information requests. He also said that some survivors do not want their personal information released publicly, not wanting to share their residential school trauma.

Sadowski said accessing the remaining documents will be crucial for First Nations, as several communities saw their records destroyed, forcing them to undertake other methods to identify potential names. “Records for the Timber Bay Indian Residential School, the Ile a la Crosse Boarding School, the Fort William Indian Hospital Sanatorium School, were some of the institutions rejected, and whose records were destroyed by Canada prior to the settlement agreement,” he said.

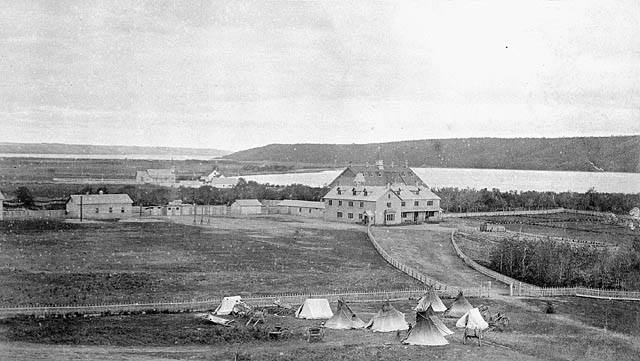

(Photo of Lebret Residental School.)

Support is available for those affected by their experience at Indian Residential Schools and in reading difficult stories related to residential school. The Indian Residential School Crisis Line offers emotional and referral services 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419.